Description

Props and Materials

Concepts

Learning Objectives

Set-Up

How To Demonstrate

Questions To Ask

Sample Dialogue

Background Information

Credits

For a paper copy of this guide, go here.

Description

This activity will explore the human microbiome. Using models of people with different colored germs on them, visitors will discover how different environments and life experiences contribute to a uniquely diverse community of microorganisms on each individual human. Visitors will then construct their own model using their own environments and life experiences, comparing their microbiomes with others to understand that everyone's is different.

(back to top)

Props and Materials

Permanent______________________________________

|

|

|

|

- 100 Human Microbiome Blank Form (click here to get form)

- stickers

- 3 model dolls: Each doll should be wrapped gently in its gray blanket and all three should be placed flat inside the plastic bin.

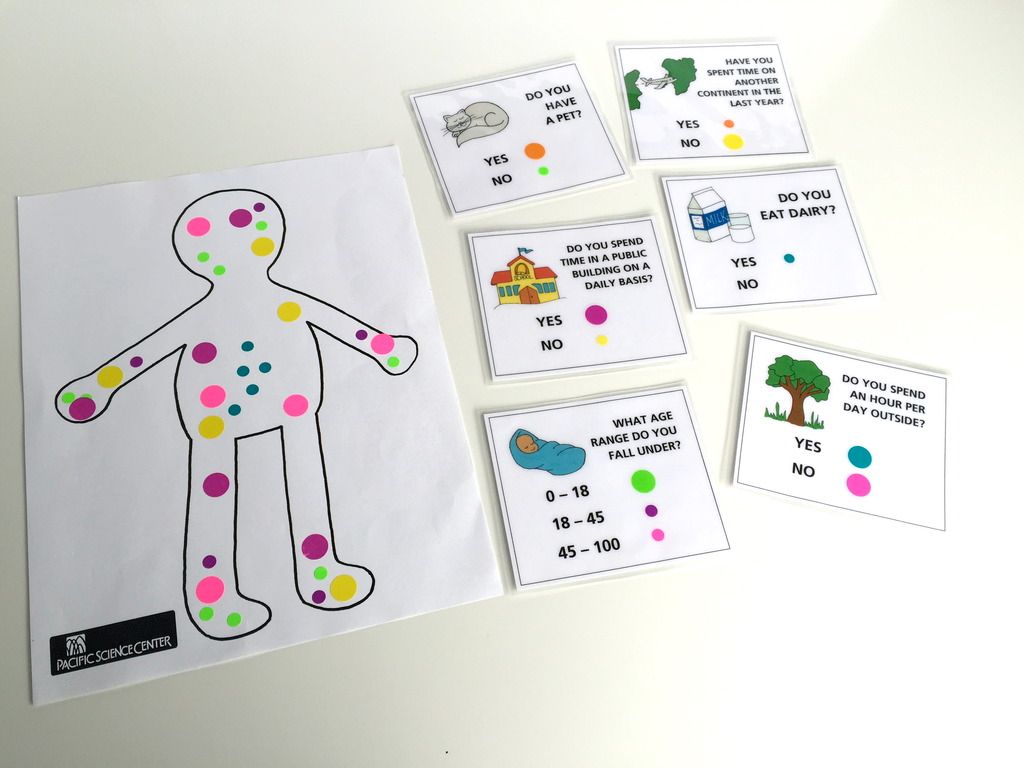

- 6 laminated cards: Store inside the cart with a binder clip to hold them together.

- Sticker rolls: Rolls should be stored in the clear bin. Ask an Ops Lead for more stickers if you run out of a color.

- Trash bin: When packing up, clean up and dispose of any trash. Empty the small trash bin if it is full.

- Human Microbiome Templates: Place blank and laminated templates back in the green envelope. Recycle any templates used and left behind by visitors.

- The dolls are not toys. While they are robust enough to be touched and held by visitors, discourage rough-housing or pulling off the fuzzy pom-poms. If any of the fuzzy pom-poms fall off, let Lauren know.

- While visitors can take as many stickers as they feel they need to put on their human microbiome paper, they cannot have extra to take home or stick to exhibits. When you have the stickers out, please keep an eye on them. They're exciting!

Concepts

- All humans are covered in tiny microorganisms called microbes, which together in and on their body is called the human microbiome. Each microbiome of each human is different from one another.

- Humans acquire microbes from everything they interact with from food to families to environment; therefore, the microbes on each human reflects where they've been and what they have done.

Learning Objectives

- Using stickers to represent microbes, visitors will answer questions about their lives and use key cards to choose microbes unique to their answers. By placing the microbes on a picture of their body to represent the human microbiome, visitors will learn that everyone has microbes all over them.

- Looking at models of people with different colored "microbes" on them, visitors will use inductive reasoning to decide how the people acquired their different microbes, drawing the conclusion that different experiences and environments lead to diverse human microbiomes.

Set-Up

- Take out one of the dolls, the 6 key cards, the human microbiome papers, and one roll of stickers.

- Have the other dolls and the rest of the stickers ready.

How To Demonstrate

- Attract visitors to your activity by asking them questions like, "Do you want to look at some germs with me?" or, "What do you think is this stuff all over this person?"

- Give them the doll and ask them what they think the fuzzy pom-poms are. Explain the pom-poms are germs, but not all germs are bad for you. The doll represents a healthy person; germs that aren't bad are called microbes. The person they are holding represents the human microbiome, which is all the microbes that live on and in a single person.

- Ask them where they think the microbes came from, and give them the card about pets. Ask them to use the card to figure out whether the person has a pet. Once the visitor has an answer, explain that every experience in life gives us different microbes. Everything we touch and every place we go is covered in different microbes, so by looking at microbes on our skin we can tell a lot about where we've been and what we've done.

- Ask them if they think our skin is the only place that has microbes. Give them the card about meat and vegetables, and ask if the person eats meat. Have them take the stomach cover piece off the person to reveal the microbes in the gut, explaining that everyone has lots of microbes in their guts. People who eat a lot of meat will have microbes that help them break down meat proteins, whereas people who don’t eat meat may have more microbes that help them break down carbohydrates. Microbes in your gut can change depending on your diet.

- Give them the other cards and help them deduce how old the model person is, whether they go outside a lot, whether they spend a lot of time in public places, and whether they have ever left the country.

- Ask them if they want to find out about their own microbiome, and give them a blank sheet of the human microbiome paper. Have them answer the questions on the cards, then put matching stickers on their paper according to their answers. Ask them if they think their microbiome will look alike or different than the model person.

- Once they have completed their microbiome, ask them to compare it to the doll and other visitors. Explain that everyone's microbiome looks different and that the diversity of microbes is healthy. Scientists have noticed that people who have the same sickness sometimes have microbiomes that look similar to each other, which scientists think means it's better to have completely unique mircrobiomes.

- Ask the visitors if they would like to look at the other dolls and use their microbiomes to deduce the life experiences of the people they represent. Encourage visitors to think about what other places and life experiences give them different microbes, and whether technology is advanced enough to use a human's microbiome to tell their life story.

Questions To Ask

- Where do microorganisms live?

- Are all germs bad?

- How many microorganisms do you think you have?

- What are some good things microbes do for our body? For the world?

- Why might it be good to have a different microbiome than someone else?

- What are some other things you have done in your life that might give you unique microbes?

- Do you think a scientist could really use your microbiome to figure out everything you have ever done? Do you think it possible a scientist do so in the future?

Sample Dialogue

Key:

- P Presenter

- G Guest

- Bold italics indicate action.

- Italics indicate a note to the presenter.

- □ indicates a cue

| P | Hi there! Want to look at some germs? | |

| G | Ew! | |

| P | This person looks sort of funny. What do you think is all over them? | |

| G | Germs? | |

| P | Right, but not all germs are bad. Have you ever heard the term microbe? | |

| G | Um . . . I think so. | |

| P | Microbes are teeny tiny life forms, so small you can't see them. Do you think this person is sick? | |

| G | Maybe. | |

| P | Microbes live everywhere, on everything--even you! They're on everything you touch, everyone you meet, and everywhere you go. So this person has picked up a lot of microbes, but are they necessarily sick? | |

| G | No. | |

| P | Great! Where do you think this person got their microbes? | |

| G | Everywhere? | |

| P | Absolutely. By looking at their specific microbes, we can tell where they've been and sometimes even what they've done. For instance, do you think this person has a pet? | |

| G | Yes, because animals are dirty and this person is dirty. | |

| P | Well, not all animals are dirty, but all of them have microbes--just like people. Even clean people have microbes! Look at this card--can you use this to figure out whether this person has a pet? | |

| G | Yes? | |

| P | You're right! Living with a pet means that some of the animal microbes might get on your skin, just like some of your microbes may get on the animal's skin. This is perfectly normal, and people without animals will have different microbes. Do you think people only have microbes on their skin? | |

| G | No? | |

| P | Let's check. Can you look inside this person's stomach? | |

| G | I guess I can rip their skin off and look. | |

| P | Great! Why do you think there are microbes in there? | |

| G | From stuff he ate. | |

| P | Definitely. Can you use this card to tell me whether this person eats meat? | |

| G | He doesn't. Which is a shame because meat is beautiful. | |

| P | Sure. Some people like it and some don't. This person doesn't eat meat, so they have a lot of this other microbe that helps him digest vegetables. Now, people who eat meat probably have this microbe too, and people who don't eat meat still have microbes that help them digest proteins, but the distribution might be really different for someone who eats meat than someone who doesn't. Can we find out anything more about this person? | |

| G | Maybe. | |

| P | Great! Are there other microbes in this person's guts? | |

| G | Yeah. | |

| P | Yeah! Why do you think that is? | |

| G | They eat other things too? | |

| P | Great! Microbes can not only tell you what someone eats, but where they go and what they do. What about this one--do you think this person goes outside a lot? | |

| G | Yes. | |

| P | Right. There are lots of microbes outside. Do you think there are a lot inside as well? | |

| G | No? | |

| P | I can see why you might think that, because we think of dirt as having lots of germs. But really there are as many microbes indoors as outdoors; they're just different. What about this one--do they go to public places a lot? | |

| G | Yes. | |

| P | Where do you think they might go? | |

| G | Maybe to school? | |

| P | Right. We're really getting to know our person! What do we know so far? | |

| G | They don't go outside but they have a pet and they go to school and they eat hamburgers. | |

| P | Yeah! What about this one--how old do you think they are? | |

| G | 73. | |

| P | Cool. Are there other microbes on here? | |

| G | Yeah | |

| P | Definitely. What are some other things this person might do that could give them different kinds of microbes? | |

| G | Maybe they don't take a bath. | |

| P | Sure. I bet if you take a lot of baths you'd have different kinds of microbes depending on where you took that bath. What else? | |

| G | Maybe they're a ballerina. | |

| P | Sure! There might be different microbes in dancing studios than there are in say, a fire station, so they might have different microbes depending on whether they're a ballerina or a fireman. Cool. All of these microbes together on a person form their microbiome. Do you think you have a microbiome? | |

| G | Yes. | |

| P | Awesome. Do you want to make your own? | |

| G | I have literally been waiting for nothing else my whole life. | |

| P | Excellent. This sheet of paper is you! Now you get to add your microbes according to your life experiences! You already told me you love meat--what color microbe should you add? | |

| G | Teal. | |

| P | Awesome. Here you go. Now, have you ever had a pet? | |

| G | I have a dog; his name is Toby and one time he ate a bunch of candy and threw up on Christmas Day and everything smelled. | |

| P | Cool! So, you have microbes just from being around your dog! Go ahead and add those. Now, do you think you go to a public place pretty much every day? | |

| G | No. | |

| P | Neat. You can add a different kind of microbe for that. Now, do you think you spend around an hour or more outside on most days? | |

| G | No. Outside is itchy. | |

| P | Okay! Maybe certain microbes bother you! You can add a different microbe for that. What about this one? | |

| G | I'm 82! | |

| P | Wow, that's nifty. Add your microbes for that. Does your microbiome look like the one we were looking at before? | |

| G | Sort of. | |

| P | Do you think there are some different things about it? | |

| G | They go outside more than I do. | |

| P | Right, that just means they have a different microbiome than you do. Do you think there are other things you do or places you go that could give you different microbes? | |

| G | No. | |

| P | Do you ever swim in the ocean? Maybe you travel to different countries. Have you ever ridden a horse? These are all things that would give you different microbes. | |

| G | Well, I only wear silk and cashmere and diamonds. Would that give me a different microbiome? | |

| P | Sure! Even what you wear might give you different microbes than other people. Do you think having different microbes is a good thing? | |

| G | Well, I'm a pretty unique individual, plus I'm awesome. So yes? | |

| P | Exactly. In fact, if you get sick, your microbiome might start to look similar to people who have the same sickness. But when you're healthy, your microbiome is going to be more different than other people's! Pretty cool, huh? | |

| G | I want another sticker. | |

| P | Okay, do you want more microbes of a particular type, or do you want to make a different microbiome? | |

| G | I want to put the stickers on my ears and pretend they're earrings. | |

| P | That sounds like fun. Do you think people with pierced ears have different microbes? | |

| G | I see what you did there. Well played, Science Educator. Well played. | |

| P | Would you like to look at some of these other microbiomes with me and find out about these people? | |

| G | Why yes, I will assist you in the identification of the highly effective habits of your doll empire. I am glad you asked. | |

| P | Thanks for looking at the human microbiome with me! |

Background Information

Click to jump to any of these topics:

Germs, microbes, microorganisms

The human microbiome

Systems biology

Studying the microbiome

Microbe distribution and diversity

Acquiring microbes

Benefits of microbes

Germs, microbes, microorganisms__________________________

Microorganism refers to any organism that is too small to be seen by the unaided eye. For most people, that’s about 0.1 to 0.2 mm. However, some people may use the term to refer to macroscopic forms that belong to a group that is largely microscopic. Macroscopic just means you don’t need a microscope to see it. Most fungi, for instance, are microscopic, so people sometimes call mushrooms (a type of fungi that is macroscopic) microorganisms.

The word microbe refers to microorganisms and viruses (which some scientists don't consider to be organisms). For this reason, the word microbe is often used to refer to microorganisms that spread disease. The word “germs” means the same thing—i.e., microorganisms that can make you sick, or microorganisms you need to wash off. Keep in mind that some younger children might not realize that the term “microorganism” includes the germs their parents tell them are bad.

Sometimes the term “microorganism” also excludes microscopic life that has differentiated tissues. Differentiated tissues are sets of cells that have different functions. For instance, in humans, cells in our heart muscles have different jobs than cells in our skin. Most microorganisms are unicellular, which means they only have one cell. Even if they have many cells, the cells are similar to each other and perform similar functions.

(back to topic list)

The human microbiome__________________________

Microbiome is a recently coined term that refers to the microorganisms in a particular environment (including the body or a part of the body). Microbiome may also refer to the combined genetic material of the microorganisms in a particular environment.

The human microbiome refers to all of the microorganisms that live on and in us. There are approximately ten times as many microorganism cells inside of us as there are human cells. According to Karlyn Beer, a researcher in systems biology:

“I wish people would acknowledge themselves as a hospitable environment for all sorts of microbial life, and that the vast majority of the microbes on us are harmless or even beneficial. Even on a human body, there are lots of unique and different environments where different groups of microbes live, and we are beginning to learn that diseases like inflammatory bowel syndromes, obesity, diabetes, yeast infections, ringworm, bacterial vaginosis and others are the unpleasant results of ecosystems out of balance. [. . .]

“It's pretty hard to wrap your head around being covered in things you can't see and can't really understand, so it's natural to be afraid or just ignore them. What's cool is that each one of us has unique microbial communities and you acquire your special collection starting at birth, and they become almost a fingerprint of your life experiences (what nurse held you when you were born? Were you born via C-section? Were you breastfed? Did you take antibiotics for acne as a teenager? How much fiber do you generally eat? What unique mutations in immune receptors are in your personal genome?)."

At its heart, this activity is about the relationship between humans and microorganisms. Dr. Beer had this to say:

“I have been fascinated since I was a kid by the idea that single microbial cells, equipped with nothing more than their own genome and eons of evolution, can be so profoundly influential. Our love-hate relationship with microbes is a testament to this fantastic diversity of human-microbe interactions... Beer and wine? Yes please! Boubonic Plague? No thanks! Understanding how a complicated community of microbes influences our health is challenging enough, and figuring out how to treat complex diseases is an even bigger challenge, especially when the communities are essentially a part of you.”

(back to topic list)

Systems Biology__________________________

While visitors may ask the names of specific microorganisms, naming individuals isn't the usual approach scientists take when talking about the human microbiome. More often they use systems biology, which is a way of looking at groups of microbes according to where they are in the body and functions they perform.

The reason systems biology is useful for talking about microbiology is that we don’t know what all microorganisms are. There are so many different species we haven’t been able to identify them all, and they evolve and change just like other life forms. Scientists can’t even identify all the species of microoganisms on just one person—there are far, far too many.

Many people know the name of a microorganisms or two—many people have heard of an amoeba in science class; they know what penicillin is; they know what cholera is because it’s a disease. These microorganisms are kind of like celebrities. We’ve heard of them and know their function because they’ve been studied extensively; however, there are millions of species of microorganisms we don’t even have names for.

For instance, many people also know the word “plankton” and “algae”. These are general terms that refer to millions of kinds of microorganisms that all have similar functions—algae photosynthesize and plankton are at the bottom of the food chain in marine ecosystems. However, there are so many different species of plankton and algae that we’ve barely even begun to identify them all. It is more useful to scientists to refer to those microorganisms as a group, all of which performs a similar function, than to refer to individual species by name.

Furthermore, many microorganisms aren’t really very important to us on an individual level. If a microorganism dies, it won’t impact our lives that much. Even if an entire species of microorganism goes extinct, it might not impact us that much, depending on the microorganism.

However, if a group of microbes that performs a function were to go extinct, life as we know it would change forever. If all algae were to suddenly disappear, we would no longer have enough oxygen to breathe. If all plankton were to suddenly disappear, all ocean life would die and then most likely many forms of land life. If all decomposers were to suddenly disappear, the world would not only be a lot grosser, but nothing would be able to grow. And if all the microbes on and in you were to die, you might die as well—or at least, you might not be the person you are now.

Because microorganisms have such a strong impact on life on Earth, it’s important to understand how they connect to other life forms, and to the Earth itself. We can understand this by learning the functions they perform in the world around us. This can help us cultivate “good” microorganisms, and help us learn how to fight against disease-causing agents. Many microorganisms can themselves be cures for other harmful microorganisms.

(back to topic list)

Studying the microbiome __________________________

The human microbial community remains largely unstudied. This is because scientists usually study microorganisms by trying to grow more, but it is very difficult to recreate the environment in, say, the human intestine. This means that the human microbiome’s influence upon human development, physiology, immunity, and nutrition are almost entirely unknown. Advances in DNA sequencing technologies have created a new field of research, called metagenomics, allowing comprehensive examination of microbial communities, even those comprised of uncultivable organisms. Instead of examining the genome of an individual bacterial strain that has been grown in a laboratory, the metagenomic approach allows analysis of genetic material derived from complete microbial communities harvested from natural environments.1.

According to Dr. Beer: “Right now, metagenomic studies are at a point where we can say ‘who's who in health and disease.’ Or, who's who among people who eat X diet vs. Y diet. Metagenomic studies are not yet at a point where we can say ‘Okay, take pills containing these four microbes, custom mixed for you, and you'll feel better.’

“To me, the biggest messages that all of these studies are saying are 1) diseases associated with microbes aren't always caused by a single pathogen, and 2) Health issues thought to be purely genetic or environmental actually have a microbiome component to them, that should probably not be ignored. Basically, we know microbial communities are related to a lot of conditions, but it's often hard to say whether it's the microbes causing the condition or the condition causing the change in microbial communities. In some cases, we do know that transferring the microbial community from organism (mouse, person) to another can change the recipient’s disease status. (i.e. there's a paper about how a lean mouse can become obese by acquiring the obese mouse's gut microbiome).

“And really, people have been messing with their microbiomes in a blindfolded way for a while—yogurt, probiotics, prebiotics—these things affect the community for sure, but the link between eating them and health outcomes is different for each person, and is not often clear or even a predictable, deterministic process. Big picture from my perspective: Pay attention to the things you do that affect your microbial communities, and health care professionals should do the same when evaluating patients. Most likely microbiome-based treatments yet to become common practice? Poop transplants. Seriously."

One of the biggest metagenomic studies ever conducted of the human microbiome was The Human Microbiome Project, a five-year study conducted by the NIH (National Institute for Health) that sequenced a great many strains of microbes on different sites of human bodies. Their website provides an interesting overview of the human microbiome and the direction of current research.

(back to topic list)

Microbe distribution and diversity__________________________

While the microbes on the dolls are spread all over the body, more often distinct groups of microbes live in distinct "sites" on the body. Sites include the inside the mouth, ear, nose, hair, and skin surfaces, including armpits, the backs of knees, fronts of knees, soles of feet, forearms, palms, backs of hands, etc.

Many studies have focused on these sites, some of which have found that microbes in specific sites are like each other and different from the microbes on other sites of the same body, and furthermore that similar sites on different bodies have more similar microbes than different sites on the same body.2. This means that microorganisms on my armpit are more different from microorganisms on the back of my knee than they are different from microorganisms on your armpit. While you and I have different armpit microorganisms, they’re still more similar to each other than they are to our knee microorganisms.

Other studies have found that the microorganisms of healthy individuals vary more than the microorganisms of ill individuals.3. This means that the microbiomes of individuals with the same illness might be more similar than the microbiomes of healthy people. This makes it hard to determine what actually makes us “healthy”, as each healthy person’s microbiome is so unique.

(back to topic list)

Acquiring microbes__________________________

We begin acquiring microbes literally as we enter this world. A baby that is born vaginally will have different microbes than a baby born by Cesarian-section; the former will acquire microbes in the birth canal while the latter will acquire mostly skin microbes. These different microbes are still apparent months and even years after birth, possibly even beyond that. Some scientists think that if we understood enough about the human microbiome, we could map every place anyone had ever been and anything they had ever done.

Babies also get very different microbes depending on whether they drink breast milk or formula. Although babies do not have a very diverse or robust microbiome when they are first born, they begin to acquire microbes from their family members and anyone close to them. Furthermore, different microbes begin to colonize different areas of the body depending on the environment those areas of the body provide—the nose, for instance, is a very different environment than the armpit. Once a baby begins eating solid food, the microbiome of the gut changes considerably.

The microbiome continues to change as a child grows older, varying more drastically in early years than it does later in life. Most children's microbiomes are very similar to their family's microbiomes; a familiy's microbiome will resemble each other more than it does strangers. Although the mother's microbiome has the most influence on a child initially, the child's microbiome will eventually grow to also resemble whoever they live with.

By the age of three the microbiome stabilizes, reaching a "baseline" state. The microbiome may still continue to grow and change, but your microbiome when you are 10 will look more similar to the microbiome you have when you are 40 than the microbiome you had when you were 5. Changes in diet and environment and disease may continue to make minor adjustments to your microbiome, while more significant hormonal changes—such as puberty, pregnancy, and menopause—may make more significant changes.

As you grow older some types of microbes become more common and others less common. Over the age of 65, the microbiome is less diverse and less robust—overall you have fewer microbes and your overall microbiome looks more like that of other individuals of similar ages.

The questions in this activity, such as whether you eat meat or whether you spend a lot of time in public, are aimed at getting guests to think what might have contributed to their microbiome and where microbes might live. Although some events, such as how they were born or who they grew up with, might have more significance in the overall formation of their baseline microbiome, these questions may be sensitive for some people. Scientists do not yet fully understand how having a pet or going to other countries may influence the human microbiome, but they do know that microbes are everywhere and that we acquire them easily, and that our different behaviors ultimately have some influence on our microbiome.

(back to topic list)

Benefits of microbes__________________________

While we do not know the functions of all the microbes that live on us, scientists are certain the gut microbes (commonly known as gut flora) "play an important role in host metabolism [...]"4. For example, gut flora is useful because it produces enzymes that our body either doesn't produce or doesn't produce enough of. These enzymes allow us to break down food molecules we might not otherwise be able to fully process, especially complex carbohydrates.5.

Scientists have also found that the microbiome (especially gut flora) plays an important role in immune response. For instance, studies have shown that the types of microbes you have my influence T-cell populations, while other microbes may help impede the development of immunity cells that are involved in allergic responses. Still other studies show that introduction to antibiotics (which kill microbes) at an early age affects development of fat, muscle, and bone.6.

These links between the human microbiome and the immune system support the idea that the microbiome plays an important part in our health and that healthy microbiomes are robust and diverse. That said, there are limitations to the studies scientists have conducted. Usually, they compare the composition of microbes in diseased and healthy individuals, which as previously mentioned can be a limited factor because we don't have enough information about healthy individuals because individual microbiomes are so varied. We also don't have enough information about how other factors such as diet, environmental exposure, and age can cause variation in the microbiome. The field of the human microbiome is relatively new and a lot more studies need to be conducted to draw better conclusions about the connections between microbes and health.6.

Another emerging field of research is about how the microbiome may not only connect with our immune system, but with our nervous system as well. There is some evidence that our microbes may even affect complex human behavior. There is in fact a vast network of neurons around our gut that helps regulate our gastrointestinal processes; early research suggests that there is a great deal of communication between these cells and gut flora.

Lastly, one of the most publicized benefits connected to the human microbiome has been the possibility of manipulating the human microbiome to improve the health of a patient by adding "healthy" microbes. Most scientists agree that fecal transplants are successful and benefit patients with conditions that might otherwise be life-threatening. However, probiotics—living microorganisms a person may digest in order to "improve" their gut flora—is an emerging field and should be treated as such by patients.

One problem with probiotics currently is that individual microbiomes are so diverse that there are probably few microbes that will prove healthy for everyone. Furthermore, as stated above, further research needs to be conducted before the human microbiome is fully understood. Right now scientists don't truly have enough information to know what 'good' and 'bad' look like.6. While some products that contain living microorganisms, such as yogurt, are advertised as "healthy" because they contain probiotics, many of these health claims are relatively unsupported. That doesn't mean you shouldn't eat yogurt, just that claims as to the health benefits of priobiotics aren't supported by research—yet. Some probiotics may even present substantial health risks.7.

(back to topic list)

(back to top)

Credits

Activity creation: Joy DeLyria and Lauren Slettedahl

Prop creation: Lauren Slettedahl

Guide creation: Joy DeLyria

Consulting: Dr. Karyln Beer

Recommended websites:

References:

1. About HMP Metagenomic Sequencing & Analysis

2. Bacterial Community Variation in Human Body Habitats Across Space and Time

3. Deep Sequencing of the Oral Microbiome Reveals Signatures of Periodontal Disease

4. Metabolic Reconstruction for Metagenomic Data and Its Application to the Human Microbiome

5. Complex Carbohydrate Utilization by the Healthy Human Microbiome

6. The microbiome explored: recent insights and future changes

7. Helping Patients Make Informed Choices About Probiotics: A Need For Research